Phygital is a scourge upon society. Not the concept, which future-minded artists obviously stand behind – the basic concept of physical meets digital, URL enters IRL – but the word itself. Phonetically ugly, it sputters out of the mouth. It connotes phlegm (ew), fidgeting (awkward), physiognomy (canceled), and although “moist” takes the prize for most uncomfortable term ever coined in the English language, “phygital” is absolutely the least chic portmanteau.

The impulse to mash together two commonly used words makes sense. How else to categorize something that didn’t exist until very, very recently? How do we use a familiar system to describe phenomena written with the language of 0s and 1s? This conundrum is a lesson applicable to web3, NFTs, and crypto-native creativity on the whole: there are times when telling, not showing, is necessary for the uninitiated. At the same time, dignity shouldn’t be sacrificed for legibility at best and buzzwordiness at worst.

The web3 community is rallying around the termination of phygital, with a host of alternatives floating in the ether. While at it, Red DAO searched for better ways to capture the phenomenon of hybrid physical-digital fashion. Below is an attempt to catalog the state of the industry, from its origins in video games and convergence with crypto, to its evolution as the potential future of mainstream fashion.

The first instances of digital clothing were far from any fashion week runway. As internet capabilities expanded, so did the concept of non-physical clothes. Kids in 2005 were playing with Webkinz, plush stuffed animals pre-registered as virtual counterparts in an online game world. FaceCake launched the first virtual dressing room in 2013, where users stood in front of a webcam and selected shift dresses and infinity scarves that hovered glitchily over their bodies. (Its retroness must be partially forgiven: the UI design was literally based on The Jetsons.) But rather than being the final destination – a worthwhile experience in itself – the dressing room was in service of online shopping customers making fewer returns. Once a user received their garment IRL, they had no reason to revisit its digital version.

It was the video game industry that proposed virtual garments as having equal or greater importance to whatever people wore while playing in their bedrooms. Fortnite, one of the most-played games on the planet, launched “skins” in 2017 as outfits for characters, priced at an average of 2000 vBucks, or $20. They hold no competitive advantage but became a joyful element of participation, an excellent example of the value of self-expression and individuality in virtual worlds.

Meanwhile, designers started experimenting with augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and other technology to make fashion that defies the laws of gravity. Brud, the company behind computer-generated model Lil Miquela, made millions from brand deals where she “wears” Pacsun, AMI, and By Far. All clothes fans could purchase and wear on the streets of L.A. that Miquela poses on. In late 2021, Dapper Labs, the prolific NFT company that launched CryptoKitties and NBA Top Shot, acquired Brud for an undisclosed sum.

It all continues to come full circle. Last year Balenciaga and Epic Games released in-game skins and outfits and physical logo-branded wares. Last month Ralph Lauren announced they designed in-game clothing for Fortnite, including a redesign of their iconic Polo Pony logo for the first time in the brand’s history. Physical Ralph Lauren merch inspired by Fortnite skins also dropped, allowing players of the mega-popular survival game to subtly signal their allegiance IRL. This month, after a four-year tenure as Ralph Lauren’s chief digital officer, Alice Delahunt bet on digital fashion with the announcement of her own company, a blockchain-enabled platform to connect emerging digital fashion talent, the mainstream fashion industry and consumers. (The only problem we’re having is the name: Syky, pronounced “psyche.”)

The landscape has bloomed so much that a pair of socks is worth 420 ETH. Sure, you could write it off as overhyped and crazy, but the point is to see beyond the physical offering. In 2019 decentralized crypto exchange Uniswap sold their first $SOCKS tokens priced at $12 as an edition of 500. Each token could be redeemed for a pair of physical socks, which meant the owner burned their original token but received a new NFT as proof of redemption. A bit of a gag, Uniswap exemplified the use of bonding curves as a price algorithm, which could easily be applied to physical goods. Other early examples in crypto include Saint Fame, the world’s first internet-owned fashion house, which similarly recreated the selling of digital tokens for physical garments on a bonding curve — or what NFT marketplace and protocol, Zora, refers to as “solving the Yeezy problem” as a way to capture secondary market value. In short, the potential market for digital to physical goods is no joke.

One of the most promising use cases for a physical item that also exists as an NFT is its traceability. A garment becomes more than what it literally is, instead assuming the history of who has created it, worn it, and sold it — all visible on the blockchain. Traditionally, the consumer journey ends at the point of sale. “Although brands will get information about the customer, to send emails for marketing material and special events, there is still no direct line of communication,” trailblazing crypto-native designer and member of Red gmoney writes, “One of the goals of 9dcc is to disrupt that.”

So the vectors that exist to form “phygital” fashion go way beyond what the term itself is capable of carrying. It’s understandable now why the community that wants the emerging technology to reach the mainstream in style are up in arms. Traversing from one plane to another, the virtual to physical, or on-chain to off-chain, requires a more sincere, elegant term. “I like the nature of the blending of the two words,” says Priyanka Desai, COO at Tribute Labs and an outspoken “phygital” hater. “We should find a word that suits the innovative form, not one that has two existing terms crashing into each other.”

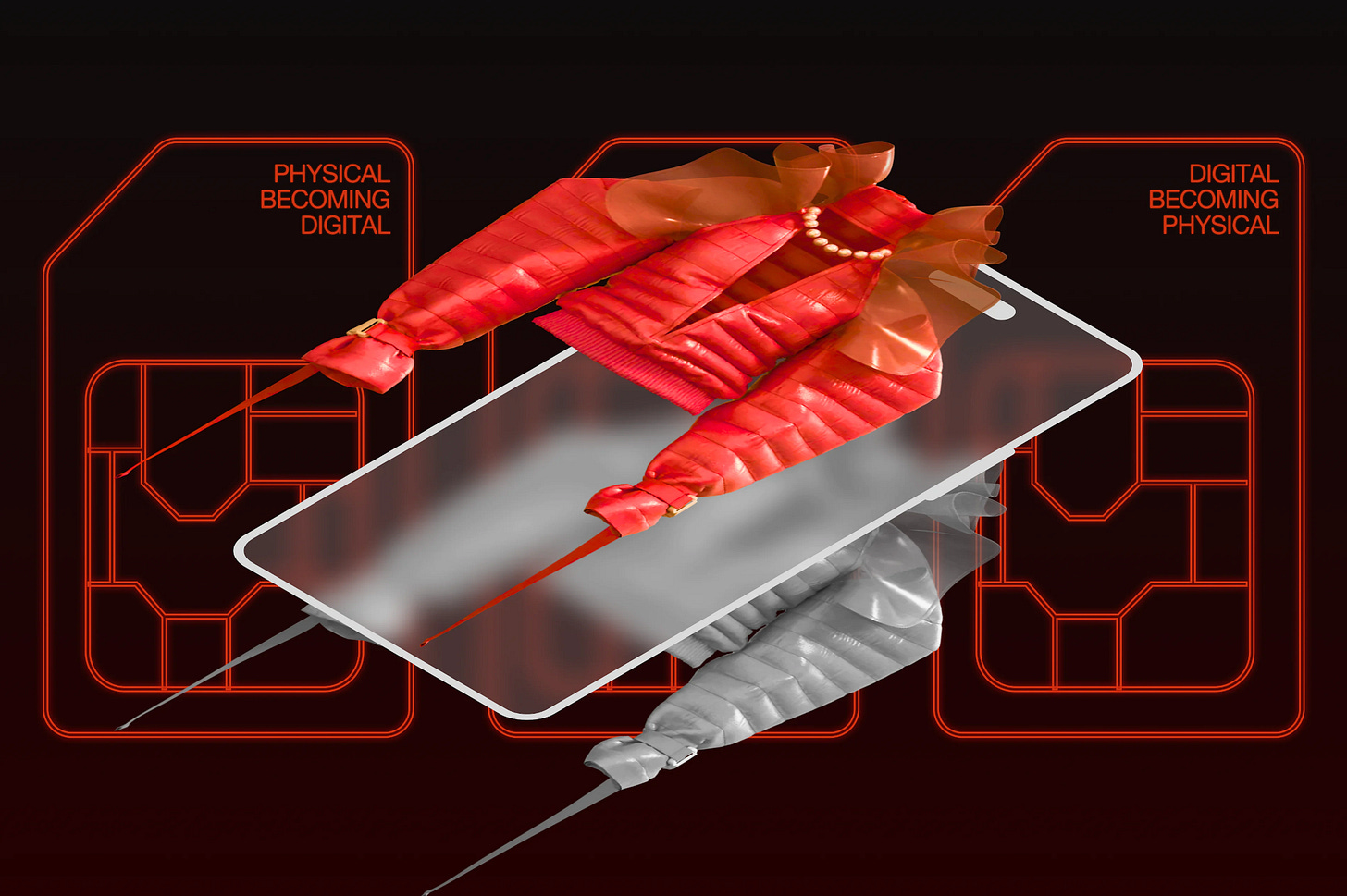

Physical-digital fashion means objects that can be worn in real-life and hold value digitally, either as a wearable in a virtual reality or as an on-chain asset that represents ownership, authenticity, proof of attendance, and other utilities.

We’ve ranked the proposals for a new term, from “most likely to be used by the crypto-fluent collector with an enviable PFP collection” to “most likely to be used by your great aunt who still asks to go to Barney’s when she’s visiting New York.”

networked product

It’s right there on the 9dcc Iteration-01 t-shirt label: “networked product.” g money, creator of the world’s first luxury crypto-native clothing brand, uses the term to describe garments infused with short-range wireless connectivity technology, allowing the “9” on the sleek black top to be scanned in order to claim the companion NFT, and to check out the ledger of provenance. 9dcc is a whole experience (which envy-inducing unboxing videos show off), requiring ownership of an Admit One NFT. If you’ve bought in, you’re really in. Art Basel Miami will see the biggest concentration of IT-01 product, and g is planning an activation involving a POAP collection competition.

metaphysical

No fooling the linguists; this is a term that’s been around since Aristotle’s day. But when one of the biggest companies in the development of an immersive virtual reality is literally called Meta, it inevitably takes on a new meaning. Not that “of or relating to the transcendent or to a reality beyond what is perceptible to the senses” isn’t relevant to the philosophy of digital fashion.

In November 2022, Artisant dropped cheeky Art Basel merch via MetaFactory, a community-owned brand creating interoperable digital wearables with physical counterparts manufactured using a zero-waste model. An embedded, waterproof HaLo (“Hardware Locked Contract”) chip by Kong bridges the worlds by allowing any smartphone to scan a garment for authenticity, plus perform other on-chain actions like signing transactions and messages. To glimpse the insignia on the edge of a hoodie feels very metaphysical, a sort of “pinch me to check which realm I’m in” moment.

hyperfashion

Let us Charli XCX-ify the little black dress, SOPHIE-fy the saddle bag. If hyperpop means a maximalist, avant-garde take on popular beats and singable melodies, then hyperfashion could mean an exaggerated expression of otherworldly possible clothing. Outfits in Decentraland skew dramatic because they can. The aesthetic is one of limitlessness: ballooning, shimmering, and shapeshifting. By affixing “hyper,” we’re mapping Baudrillard’s concept of “hyperreality” onto a form fit to wear. Rather than beginning with the physical, digital fashion takes precedence in our overwhelmingly simulated reality.

physical backed token (PBT)

Azuki, the digital brand known for an anime-themed NFT collection of 10,000 avatars which had one of the most successful drops in crypto history, launched their “physical backed token” in October. A cryptographic chip shaped like a little lima bean was seared into 50 golden skateboards, 24 karat in real-life and highest-definition graphics in virtual reality. “Digital tokens representing physical items already exist, but the two are often decoupled after the mint,” the team writes. “PBT is a standard which features decentralized authentication and tracking of the ownership lineage of physical items, completely on-chain and without a centralized server.” We support the concept of digital backed by physical, suggesting digital is primary, given our hunch that the value of these assets will soar beyond that of traditional, clothing-hanger fashion.

metareal

Technical fashion designer Charli Cohen has been playing with materiality and realness since she was 15. She’s exacting about how garments look and feel, a necessity for performance wear, while believing that the metaverse is equally “real.” Maybe we should think about the broader definition of material: something to work with, to use as a tool toward a greater creative end.

digital twin

This one gets at the hope for greater opportunities for self-expression online with more and more designers switching off between Browzwear and their sewing machine. It’s a beautiful image: to envision your metaverse avatar wearing your favorite IRL outfit down to the stitch. “Digital twin” is what experimental musician Holly Herndon calls her custom AI vocal instrument and interface that allows users to input lyrics and, within minutes, receive a track “sung” by Herndon’s intentional deepfake. “Holly+” is going on an adventure all on her own, the way a video game character lives their life while the player is away.

Castle Island Ventures’ Nic Carter blogged this summer that digital twin “implies a distinction and a mirroring, whereas the ultimate objective should be to get collectors to think of the NFT and the physical good as inherently the same thing, just existing in different metaphysical realms.” It’s a matter of intention; for Herndon, the digital twin is supposed to be distinct because of its new context. “When you liberate a sound from its source, you also liberate it from its context,” she told The FADER in response to the ethics of an AI bot trained on Travis Scott's music without the artist's consent. “In my opinion, context still matters. It's where something comes from. It's the human beings that made it. It's the cultures that cultivate it. It's the spaces, the physical spaces that housed it.”

forged fashion

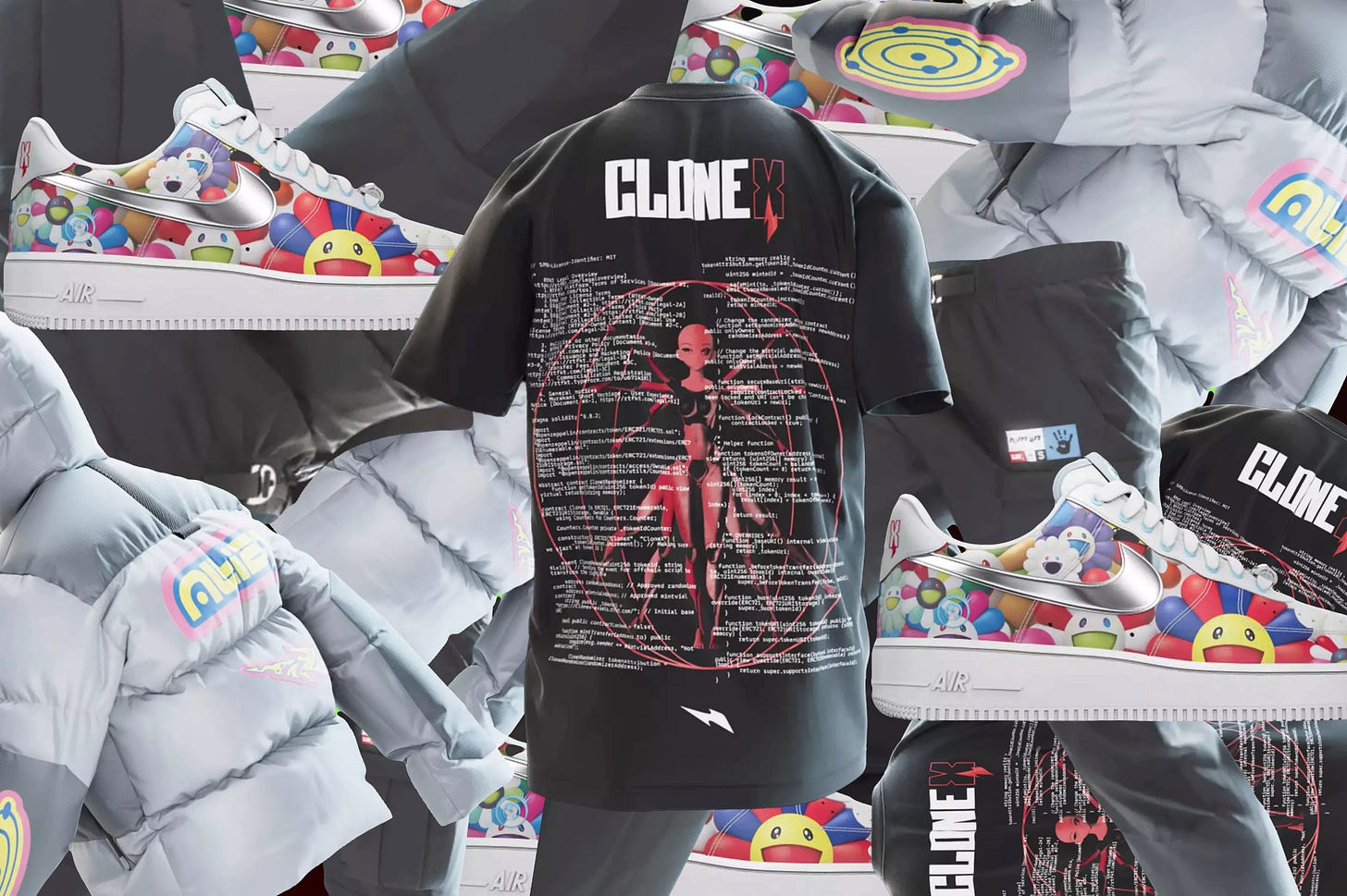

Some folks in the RTFKT community call their recent collaborations “forged fashion” – take, for instance, the conversation around the first-ever blockchain-confirmed sneaker, a Nike Air Force 1 that exists on hypebeast’s feet and on OpenSea. In blockchain technology, forging is a form of proof-of-stake consensus, as opposed to proof-of-work, which relies on centralized miners. This resonates with the goal for many designers working between digital and physical worlds: to create tools for identifying digital friends IRL, other people down for the cause. POAP, or “proof of attendance protocol” involves NFTs that represent the fact that the recipient personally participated in some event. Garments with an embedded POAP are proof-of-stake in their own way, with the owners reaping the reward of participation.

entangled NFTs

Bennett Collen, CEO and cofounder of web3 footwear and fashion brand Endstate, uses “entangled,” a term borrowed from particle physics. He explains it as “two things that even across great distances have knowledge of each other and can’t be described independently of one another.” Nothing exists in a vacuum, especially not crypto. Some physical NFTs are rigged to automatically collect loot when, say, the item enters the wireless field of another owner from the same collection. Then there’s the reverse, where an NFT entitles someone to real-life perks. In August, CryptoPunk owners had the opportunity to purchase up to three NFTiffs, which could be redeemed for real-life diamond pendants. Once all was shipped and done, the NFTiff became a certificate of authenticity that reflects the likeness of its owner’s bespoke pendant, or, if not redeemed, a digital collectible in a wallet.

futurecraft

Artist Robert Panepinto is a glassmaker now using the medium primarily as an asset to create NFTs. In his moody, contemplative #beings collection, “gathered from the 2000-degree furnace, sculpted glass becomes digital avatars [...] to live in peace with other digital friends.” Owning one #beings NFT is equivalent to holding one raffle ticket to win a physical glass sculpture blown by Panepinto. He coined “futurecraft” to describe coexisting digital and physical workflows, as he is a believer in digital as the new frontier and craft as an ancient form that’s never going away. We like the implication of a craft maker that the term engenders, a reminder of the process and a proposal for a new meaning of “made by hand” in a digital world.

full-stack consumer products

Carter created his own favorite term, “full-stack consumer products,” to denote items where the owner has full access to all its elements. This is tricky because of the slight differences in how creators choose to sell physical NFTs: a burn-to-redeem model, for example, necessitates losing an NFT to receive a physical product, whereas redeem-to-retain lets an NFT holder redeem their token to receive a physical product while keeping the NFT.

The physical is becoming digital, the digital is becoming physical, and the scope of possible outcomes for how this shift will impact culture over the coming decades is unfolding in real time. Language frames our collective understanding of this new world — it’s a seminal accessory to our emergent industry. There’s countless examples of web3 fumbling the bag when it comes to choosing words that make sense to people outside of the space (i.e. DAOs, NFTs, and “wallet”), and we want to make sure that when digital / physical fashion’s time comes, it arrives in style.